Despite continuing elevated unemployment and dampened consumer confidence, the housing market has been surprisingly strong in the months following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the U.S. Commerce Dept., single-family housing starts for August were estimated at the seasonally-adjusted annual rate (SAAR) of 1.01 million units, up 4.1% from July and 12.1% from August 2019. This represented the highest level for single-family starts since May 2007. Similarly, new home sales for July were estimated to be 901,000 units, up 20% from June and 36.3% from July 2019, the highest level for new home sales since April 2007.

The strength in both measures of housing market conditions reflects both the rebound from pandemic-related lows in April and seasonal adjustment factors which probably do not take into account the shift in sales from the peak of the spring selling season in March and April to the recent summer months. While the seasonal adjustment factors may distort the magnitude of the rebound, the actual, non-seasonally-adjusted data indicate that single-family starts are up 3.8% through August and new home sales are up 8.4% through July year-to-date, which is still much stronger than I had expected, given that the current rate of unemployment is more than twice the pre-pandemic level and consumer confidence has not rebounded from its post-pandemic plunge. This strength probably reflects the benefit of the decline in mortgage rates to historically low levels and the desire by some apartment dwellers to move into single-family housing to reduce their risk of COVID-19 and embrace the new work-from-home lifestyle. Without a significant rebound in employment and consumer confidence, however, these benefits for housing are likely to prove temporary.

The strength in the national housing data is also reflected in homebuilder new order trends. On average, the eleven homebuilders that I follow reported 2020 second quarter growth in new unit orders averaging 9.9%, down modestly from the average 12.0% increase in the first quarter. Yet, the range of the reported individual percentage changes in new orders was unusually wide due to the timing of reporting. Builders with a May 31 quarter end posted order declines for the quarter, while most builders with June 30 quarter ends posted gains, several of which were in excess of 30%.

Despite the rebound, the group on average does not look particularly expensive at 11.3 times projected 2020 earnings and 9.4 times projected 2021 earnings. The question, though, is whether the builders will be able to deliver on the consensus views. Anecdotally, some of the builders have indicated that they will not be able to expand their deliveries commensurately with new orders anytime soon because of factors such as availability of materials and labor and the restrictions placed upon housing construction as a result of the pandemic. If the factors that have driven new home sales and new orders prove to be temporary, homebuilding stocks could experience further declines.

The August 2020 SAAR of single-family housing starts was up 15.6% over the prior year. July’s SAAR of new home sales was up 36.5% over the prior year and the current consensus estimate of 875,000 for August would be up 23.6% over the prior year. Even though two builders, Toll Brothers and Meritage announced in late September that their quarter-to-date new unit orders were up 110% and 73%, respectively, that pace of growth is not likely to be sustainable beyond the next few quarters at best.

If I assume that actual orders for the remaining months of 2020 are on a glide path to a zero percent year-over-year increase by the end the year, single-family starts will total 922,000 units in 2020, up 3.9% over the 888,000 units posted for 2019, and new home sales will total 748,000 units, up 9.7% over the 682,000 units recorded in 2019. That is still an amazingly strong showing, given the sharp drop in starts and sales from the end of March to around mid-May; but it is a more modest pace of gains than the numbers that we are currently seeing out of the Commerce Dept. and from the individual builders.

Much of the strength in housing is due to the steady decline in mortgage rates, as shown in the chart on the next page. Mortgage rates were at the highest level for 2020 going into the year and have been declining ever since, continuing a slide that began in November 2018, right before the Federal Reserve reversed course on its interest rate normalization policy. According to Freddie Mac, the average rate on a 30-year mortgage was 2.87% during the week of Sept. 17, down nearly a full percentage point from the 3.72% recorded on Jan. 3. Although it appears that mortgage rates may be bottoming, the spread between the 30-year mortgage rate and the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield is currently 217 basis points (bp), well above the long-term average of 180 bp. Consequently, it is possible, but probably unlikely, that the average 30-year mortgage rate could still decline, perhaps by as much as 37 bp in the weeks ahead.

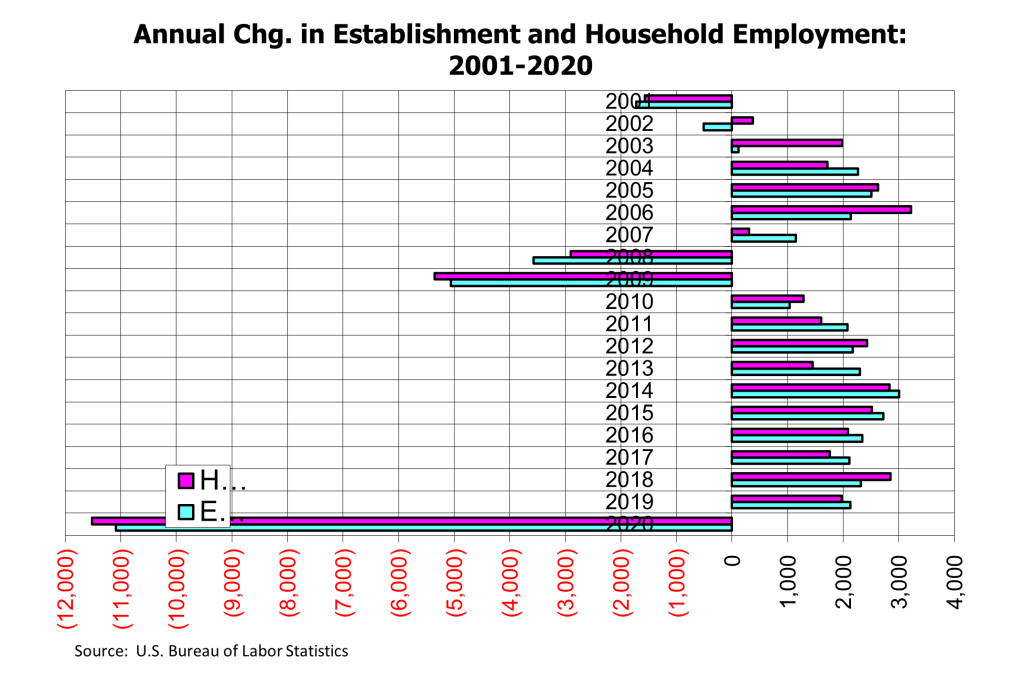

As noted, housing has been quite strong in the face of weakness in economic measures, like employment and consumer confidence, that have traditionally been key drivers of housing demand. Despite significant gains in recent months, both payroll and household employment are down by more than 11 million jobs since the beginning of the year. The rate of unemployment, last measured at 7.9% for September, is more than twice the 3.6% rate recorded in January.

By definition, in order to add a house to the housing stock, there must be a household to occupy it and at least one household member must be employed. Expansion of the housing stock can be supported by households switching from renting to owning, but the Commerce Dept. reported that the U.S. rental vacancy rate declined to 5.7% in the 2020 second quarter from 6.6% at the end of the 2020 first quarter and is now well below its ten-year average of 7.7%. Some sources suggest that rental vacancies will increase in the months ahead; but most say that the increase will be due to rent defaults and evictions, which implies a potential shrinkage in households, for example, as some renters move back in with their parents. Reports of renters moving out of apartments and into single-family houses to escape the pandemic and adapt better to the work-at-home imperative may be true, but there is no clear evidence that this has been a big driver of single-family housing demand or that this trend is likely to continue.

The other key driver of housing demand has traditionally been consumer confidence. Here too the evidence does not support strength in housing. According to the Conference Board, the broadest measure of consumer confidence declined to 84.8 in August from 91.7 in July. That measure had rebounded to 98.3 in July, but it has fallen back over the past two months. At the most recent August reading, consumer confidence was actually slightly below the 85.7% recorded in April 2020, during the early weeks of the onset of the pandemic. (Since this report was originally published, the Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence index was reported to have rebounded to 101.8 in September, from a revised reading of 86.3 in August.)

Despite this conflicting data, homebuilding stocks have rebounded sharply from their March 2020 lows. My index of 11 publicly-traded homebuilding stocks nearly tripled from March 20 to August 21, to a level 8% above the pre-pandemic high posted on February 21. Since then, homebuilding stocks have slipped back and are now struggling to hold on to their gains. At the very least, it should not be surprising to see a correction after such a sharp and quick run-up.

From here, though, if the homebuilding stocks are to post further sustainable gains, it would seem only logical that the economic fundamentals must become supportive of continued growth in housing production. One potential catalyst could come from a return to employment of most of the 11 million or so that are still out of work. Yet, it would be reasonable to assume that these people will not run out on their first day of returning to work (or getting a new job) to buy a house. They may very well have to catch up on past due bills and gain the necessary confidence that the job that they are returning to (or have just landed) is likely to be permanent.

If the recent rebound in housing has been driven by the 90% or so of the working population that remained employed throughout the pandemic, it is reasonable to think that much of this demand represents the pulling forward of purchases that might have taken place over the next year or two. Buyers may have rushed to buy in order to lock in that low mortgage rate or to get a better deal on that house that they had been eyeing. The question though is whether those likely future buyers will be replaced by a sufficient number of new buyers to avoid a flattening or decline in housing demand in the future. In order for that to happen, it would seem that the economy would have to bounce back strongly and sustainably. Although consensus estimates anticipate that the U.S. economy will grow above trend at around 3.0%-3.5% in 2021 and 2022, after falling 5% or so in 2020, economic growth in 2023 and beyond is currently expected to ease back to the anemic pre-pandemic levels of around 2%.

As noted in my summary, the average builder reported an increase in net new orders of 9.9% in the 2020 second quarter, less than the 12.2% gain recorded in the 2020 first quarter. The dispersion of individual builder tabulations against the average was exceptionally wide, however, based mostly on the timing of quarter end. For example, KB Home and Lennar, who’s fiscal second quarters ended on May 31, posted declines in new orders, while the remaining builders with June 30 or July 31 quarter ends, posted gains. In several cases, those year-over-year June quarter order gains exceeded 30%. Based upon recent reports and advance press releases, average order gains for the 2020 third quarter should be in excess of 20%, possibly in excess of 30%.

Despite housing market performance that appears to be well out of sync with broader economic trends, the management teams of the publicly-traded homebuilders remain optimistic about the outlook for housing. The NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Market Index, a measure of homebuilder sentiment about current and future sales expectations, rebounded to 83 in September, the highest level ever recorded, from a recent low of 30 in April.

On recent earnings conference calls, the homebuilders provided color and commentary on current and evolving market conditions. All said that they had experienced a sharp drop in demand during April, followed by a recovery in May and acceleration in June. They attribute the increase in demand to low mortgage rates, the desire to improve their living conditions both to escape the pandemic and also to embrace the shift to work-from-home which many see as continuing. They also are benefiting from the limited inventory of existing homes. (So the recent surge in sales represents an increase in market share for newly-constructed homes.) Finally, they believe that millennials, who are now in their prime home buying years, are more desirous of living in single-family homes.

Although nearly all of the builders report that the surge in sales in June has continued in July and August, many of them were still cautious in their outlook for the housing market, given the persistence of the pandemic and its potential long-term effects on the economy. Many touted their “build-to-order” business models, which prevent them from getting over extended. (Yet, many have also said that having “move-in ready” speculative homes has allowed them to capture sales quickly from buyers who are eager to move.) On the second quarter calls, most of the builders noted the continuing challenges of building and delivering homes, given the restrictions necessitated by the pandemic. Thus, they planned to remain disciplined in their land buying activities, for example, by increasing their use of land purchase options as a way to gain control over land while limiting risk.

As a result of all these factors, most of the builders said that they were guarded in their response to the recent surge in buying demand. Rather than take steps to expand their selling platforms (and fixed costs) in response to the sharp rise in demand, they would seek to assess the sustainability of that demand over time to ensure against becoming overextended. Consequently, investors will be listening for whether that conservative approach has changed during the upcoming round of third quarter earnings conference calls.

Another key metric to watch is the pace of home closings vs. orders. While we know that order growth will be strong, it is unlikely that growth in home deliveries will be nearly as strong, due to pandemic-related construction delays, including availability of labor and materials (including lumber) and the paced scheduling of subcontractors. Hopefully, the builders will provide some guidance on when the pace of deliveries will begin to catch up to new orders.

In my previous housing market update, published in June, I similarly expressed caution in the outlook for the housing sector and homebuilding stocks. Clearly, new order activity, both on the national level and on average for the homebuilders, has been much stronger than I anticipated. Consequently, the homebuilding stocks continued to significantly outperform the broader market from mid-June until mid-August. Despite that surprising strength, I remain cautious in my outlook for both. As noted above, I believe that the recent strength in national single-family starts and new home sales has been amplified by seasonal adjustment factors that are out of whack as a result of the pandemic. While it may not be easy to accurately adjust these seasonal adjustment formulas, it is surprising that the Commerce Dept. has not alerted its readers about the potential impact of the change in seasonal buying patterns. Consequently, if and when the Commerce Dept. does address this issue, housing-related stocks could suffer a modest setback.

At the same time, the homebuilding stocks appear to be entering a correction that could take average prices down another 15% or so. If that does happen, the sector’s ability to rebound and eventually post higher highs, will, in my opinion, depend upon an improvement in the broader economic outlook, which from a fundamental perspective is necessary to support a sustained recovery in the new homes market. At that point, homebuilding stocks could go on to new highs, especially since, based upon their recently reported financial results and the current consensus estimates, they do not look especially expensive, even after the recent run-up.

October 8, 2020. (Report originally published on Sept. 21, 2020)

Stephen P. Percoco

Lark Research

839 Dewitt Street

Linden, New Jersey 07036

(908) 975-0250

admin@larkresearch.com

© 2015-2025 by Stephen P. Percoco, Lark Research. All rights reserved.

This blog post (as with all posts on this website) represents the opinion of Lark Research based upon its own independent research and supporting information obtained from various sources. Although Lark Research believes these sources to be reliable, it has not independently confirmed their accuracy. Consequently, this blog post may contain errors and omissions. Furthermore, this blog post is a summary of a recent report published on this subject and that report provides a more complete discussion and assessment of the risks and opportunities of any investment securities discussed herein. No representation or warranty is expressed or implied by the publication of this blog post. This blog post is for informational purposes only and shall not be construed as investment advice that meets the specific needs of any investor. Investors should, in consultation with their financial advisers, determine the suitability of the post’s recommendations, if any, to their own specific circumstances. Lark Research is not registered as an investment adviser with the Securities and Exchange Commission, pursuant to exemptions provided in the Investment Company Act of 1940. This blog post remains the property of Lark Research and may not be reproduced, copied or similarly disseminated, in whole or in part, without its prior written consent.