Non-GAAP financial measures are alternative measures of a company’s financial performance that are derived from GAAP (generally accepted accounting principles). They provide investors with additional information and insight into a company’s historical and future financial performance, financial position and cash flows.

There are several types of adjustments that are made to GAAP results to produce the non-GAAP adjustments. These include:

- One-time, unusual and nonrecurring charges;

- Items that are considered non-cash

- Items that are not related to business operations (for example, acquisition-related costs or unusual litigation costs);

- Adjustments to reflect results that are more representative of how the business is managed; and

- (sometimes) Corrections of perceived flaws in GAAP or the effects of implementation of new accounting standards that companies feel do not accurately portray their performance.

Some commonly used non-GAAP measures are adjusted earnings per share (EPS), earnings before interest, taxes and depreciation (EBITDA) and its variants, and funds from operations (FFO).

Many companies say that non-GAAP financial measures (NGFM) help them explain the performance of their businesses. The NGFMs are often used by companies internally to measure their performance and to determine executive compensation and bonuses. They help strip out the noise associated with one-time events, which may be a better representation of the ongoing operating performance of the company. They also adjust for GAAP requirements that they believe distort true performance.

Management generally decides which non-GAAP financial measures are used and how they are calculated. There is generally no standard definition or standardized method for calculating NGFMs. There are also no audit or financial controls requirements.

NGFM’s have become institutionalized. They are now part of the infrastructure of performance measurement. According to the accounting firm PwC, 97% of S&P companies presented at least one NGFM in 2018, up from 59% in 1996.

These measures often drive short-term movements in stock prices. Adjusted EPS, for example, is the measure most used by the business media to assess quarterly financial performance and especially whether companies have exceeded or fallen short of the consensus or mean estimate.

Many NFGMs, such as adjusted EPS, provide a more favorable presentation of earnings results. This obviously can result in a higher stock price, which may be the primary reason why companies use them. Sell-side analysts and investors with long positions in stocks may also have an incentive to encourage the use of NFGMs.

In a 2019 op-ed in CFO Magazine, Drew Bernstein, co-managing partner at Marcum, Bernstein and Pincus, an independent accounting firm, asserted that the most common response of companies to the question of why they use NFGMs is that these measures are requested by analysts who use them in preparing their financial projection models for valuation purposes.

The use of NFGM is also controversial. One prominent hedge fund manager says that NFGMs constitute “legal fraud.” Others suggest that a race to the bottom is at play. Adjustments have become so pervasive that the share prices of companies who utilize more conservative performance measures may suffer a valuation discount compared with their more aggressive peers.

Mr. Bernstein suggests this race to the bottom will not be ended until users of financial statements – institutional investors, analysts, lenders and the media – agree that we are on the verge of systemic failure in financial reporting. Such agreement would apparently create the impetus for change.

History of NFGMs. The first non-GAAP financial measures appeared in the early 1970s, according to the SEC. But they did not begin to become rooted in the fabric of financial reporting until 1988, when Standard & Poor’s introduced a NFGM called “operating earnings” – i.e. earnings excluding certain extraordinary or unusual items – for the S&P 500.

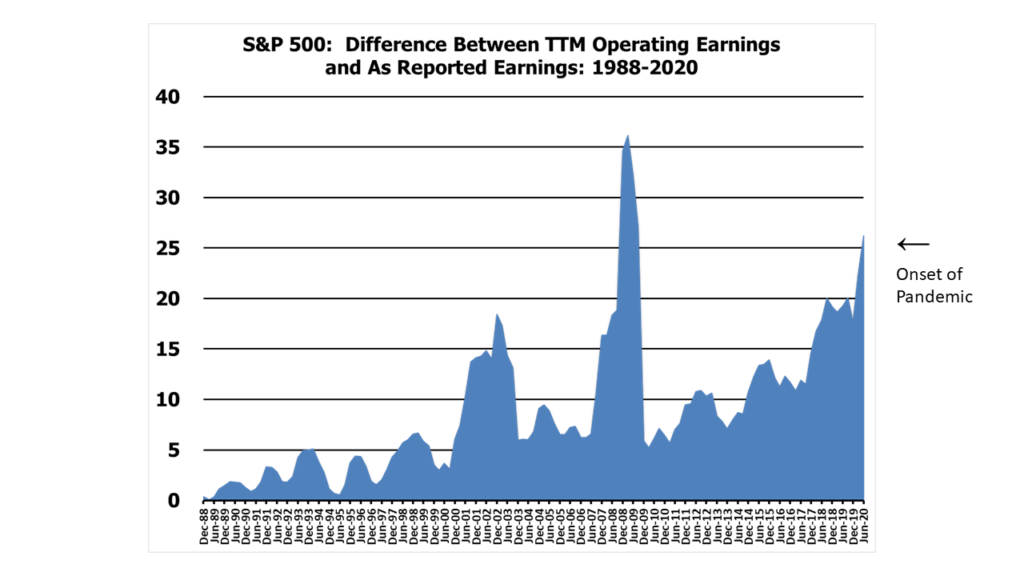

Since S&P initiated the measure, the difference between GAAP and operating earnings for the S&P 500 has increased over time, especially over the past several years. Spikes have occurred around recessions, when many companies record increased operating losses and impairments. The most recent spike in 2020 was precipitated in the early months of the pandemic. Data in the table above are up through the 2020 second quarter.

Non-GAAP controversies first arose during the “dot-com” technology bubble, especially following the failures of Worldcom and Enron. This resulted in the adoption of the Sarbanes Oxley Act, one of whose provisions directed the SEC to address the practice. The Commission issued Regulation G, “Conditions for the Use of Non-GAAP Financial Measures” in 2003.

Through Regulation G, the SEC mandated the following with respect to the use of NFGMs: An NFGM, together with its accompanying information and disclosures, cannot be misleading. NFGMs must be presented along with a disclosure and reconciliation to the most directly comparable GAAP measures. The NFGM must not be disclosed more prominently than the comparable GAAP measure. Finally, NFGMs must be accompanied by disclosure stating the reasons why management believes that they provide information that is useful for investors.

Regulation G was followed in 2010 by the SEC’s first set of Compliance and Disclosure Interpretations. Presented in a question and answer format, these C&DIs addressed many of issues that arose from financial statement preparers about defining and utilizing NFGMs.

In 2016, there was a flurry of activity from the SEC and others that arose in response to the relentless growth in the use of NFGMs. In May 2016, the SEC issued an extensive second round of C&DIs. At that time, NFGMs also received widespread coverage in the media and the CFA Institute issued its first position paper on the topic.

The Value of NFGMs. Despite the SEC’s justifiable concerns about NFGMs, these measures do provide investment professionals with useful information to aid the analysis of a company’s performance and future prospects.

Some supporters of non-GAAP financial measures assert that they provide a better assessment of a company’s “core” or future sustainable earnings (and cash flows). This is especially true if the excluded items are truly temporary and/or non-cash in nature. Specific revenue and expense items that are included in non-GAAP adjustments are often not disclosed in any other company communications or SEC filings.

Yet, there are often potential pitfalls in using these measures.

S&P 500 Operating Earnings. This measure helped to institutionalize the adoption of NFGMs. It is widely used in the calculation of a price-to-earnings ratio for the S&P 500, which is a key measure of the valuation of the equity market.

Yet, it is hard to find a precise definition of S&P 500 operating earnings. A search of the term “S&P 500 operating earnings” yields interpretations from numerous third party sources of varying degrees of comprehensiveness. I have not been able to find an official definition of the term from Standard & Poor’s.

Accordingly, I believe that investors should proceed with caution in using S&P 500 operating earnings as a valuation measure.

EBITDA or earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization is the most widely-used non-GAAP metric. EBITDA is also often called “operating cash flow.” It is meant to provide a measure of the cash generated by a company without regard to its debt costs or tax policies. Accordingly, it is a measure that facilitates valuation comparisons among companies with different capital structures within a given industry.

The primary flaw with this measure is that it adds back depreciation (a non-cash expense) without considering the capital costs required to sustain operating cash flow. For that reason, some companies also disclose “maintenance” capital expenditures or that portion of total capital expenditures that is deemed necessary to sustain profitability. These maintenance capital expenditures are separated from “growth” capital expenditures, which are incurred to grow profits, cash flows and EBITDA. Expenditures for acquisitions are not deducted in calculating EBITDA because they are considered to be similar to growth capital expenditures.

There is no standard definition of maintenance capital expenditures. I do not know of any company that describes how it distinguishes maintenance from growth capital expenditures. Consequently, investors have no assurance that the level of capital expenditures designated by a company as maintenance is actually sufficient to maintain its EBITDA.

Some capital expenditures may be classified as growth when they might rightfully be considered maintenance. For example, capital expenditures for a new product that is intended to replace an existing product that is becoming obsolete might justifiably be considered maintenance, because they help maintain the company’s profitability by offsetting the decline in profits from a mature product nearing the end of its life cycle. By similar reasoning, acquisitions made to replace old products or product lines may also be akin to maintenance capital expenditures.

Distinguishing between maintenance and growth capital expenditures requires careful consideration, utilizing information that is not generally available to public company investors. Without improved disclosure, it seems to me that one (and perhaps the only) way to determine the true nature of capital expenditures is to assess whether the company is achieving profit growth that is commensurate with its level of capital expenditures. This might also involve an evaluation of the trend in investment performance measures, such as return on capital employed.

Although many analysts, including myself, use EBITDA multiples to compare valuations of companies within an industry, such analyses are imperfect because they do not consider whether each company’s capital assets are in good operating condition and what expenditures are required to keep them that way. It is likewise risky to use EBITDA alone as a measure to assess a company’s ability to service its debt without also factoring in an estimate for required (or maintenance) capital expenditures.

Funds from Operations (FFO) is another non-GAAP metric used exclusively by real estate investment trusts (REITs) to gauge their performance. FFO is defined simply as net income plus depreciation on real estate assets. “Normalized FFO” is FFO excluding unusual items such as impairments, acquisition costs and debt extinguishment costs. “Adjusted FFO” is normalized FFO minus other charges that are typically included in non-REIT non-GAAP calculations, such as non-real estate depreciation and stock compensation expense. Some companies also subtract out maintenance capital expenditures to arrive at adjusted FFO.

FFO is considered a rough proxy for REIT taxable income, of which 90% must be distributed to equity investors annually in order for the REIT to maintain its tax exempt status with the IRS.

The basic definition of FFO is determined by the National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts (NAREIT). The use of FFO per share in public disclosures and SEC filings was approved by the SEC in the May 2016 C&DIs. However, the SEC has not explicitly approved the changes that NAREIT made to the definition of FFO in 2018.

The original premise behind FFO is based upon the notion that depreciation frequently overstates the cost of maintaining real estate properties. Real estate assets are long-lived and properties can often operate for many years without having to undertake major repairs or upgrades. Thus, many REITs should generate more cash than earnings, resulting in surplus cash that can be distributed safely to shareholders without compromising the sustainability of cash flow over time.

Even though many REITs disclose their maintenance capital expenditures, however, it is not clear whether their assessments are accurate. Property upgrades may be important in certain real estate classes, such as hotels, in order to maintain their competitive edge. In certain categories of real estate, therefore, it may not be enough to ensure that the roof does not leak. It is often difficult for outsiders to determine whether a REIT is spending enough to maintain its competitiveness.

Stock-Based Compensation Expense. Many companies include stock-based compensation expense in their non-GAAP earnings because it is non-cash. Technology companies, in particular, have included stock-based compensation in their EPS adjustments, because this has traditionally been a large cost especially for start-up companies that may distort the growth in earnings and cash flow that they are achieving in their early years. Yet, many technology companies continue to exclude stock compensation costs from profit measures well past their start-up phases, even as they have evolved into mature companies.

Although stock-based compensation is non-cash, it nevertheless has value and affects shareholder returns. For that reason, I believe that it is generally not appropriate to add back stock-based compensation in the determination of adjusted or non-GAAP earnings. However, it is acceptable for debt investors to add back stock-based compensation in their determination of EBITDA or cash flow available to service debt, except in situations where a company has adopted a policy of expending cash to buy back the increase in shares caused by the issuance of stock-based compensation.

Adjusting “Non-Cash” Expenses for the Associated Cash Expenditures. Like EBITDA, there are a number of “non-cash” expenditures that are often included as adjustments in the determination of non-GAAP earnings, but for which the associated cash expenditures are excluded. For example, some mining companies treat the accretion of their asset retirement obligation liabilities as non-cash in non-GAAP calculations, but they do not then include or add back the actual cash payments made to meet those obligations.

Amortization of other capitalized costs, such as software- or marketing-related expenses, if included in the determination of any “non-GAAP” measures, should likewise be offset by the corresponding cash expenditures made for those line item categories for the period.

Similarly, earnings on unconsolidated equity investments are non-cash and thus should be excluded in calculations of EBITDA or non-GAAP earnings, but the actual cash distributions received on those investments (e.g. dividends) should be included in those measures.

The same can be said for certain unrealized gains and losses on derivatives and hedging programs. These unrealized gains and losses can add volatility to reported results, especially during periods of wild swings in commodity prices. For that reason, excluding those unrealized gains can provide investors with a better picture of a company’s base performance, as long as the realized gains and losses are included when they occur.

The Problem of Recurring Non-Recurring Expenses. One of the primary rationales for non-GAAP measures is to adjust for so-called non-recurring expenses. Examples include restructuring costs, acquisition-related expenses and unusually high litigation costs. Because these are considered non-recurring, they are disclosed to provide a better perspective on future earnings prospects.

It is often the case, however, that such expenditures are not non-recurring. Restructuring is an ongoing process in many businesses. It may make sense to adjust earnings for unusually high restructuring costs in a given year in order to prepare a more realistic forecast of a company’s future performance, but regularly recurring restructuring costs should be considered an ongoing cost of the business.

Perspective Drives the GAAP vs. non-GAAP decision. Analysts should parse non-GAAP earnings to inform their assessments of a company based upon the type of securities that they are analyzing and the time frame of their analysis. As noted above, adding back non-cash stock-based compensation costs may be more appropriate for the debt analyst who is primarily concerned about the adequacy of the company’s cash flow to service its debt, than for the equity analyst, because shareholders bear the cost of such compensation.

Use GAAP to Evaluate Historical Results and Non-GAAP Adjustments to Inform Your Projections of Future Financial Performance. NFGMs can help guide those who are looking at a company prospectively; but GAAP earnings are more relevant for an analysis of historical performance. Non-GAAP earnings can form the base upon which projections of future performance can be built, assuming of course that the adjustments to GAAP earnings are truly “one-time” or non-recurring in nature.

When evaluating historical results, the GAAP numbers, adjusted perhaps to smooth lumpy charges (by spreading them out over multiple years), are a better indicator of performance. Impairment charges, for example, are a non-cash expense that is usually taken against an asset for which there was a previous expenditure of cash. By ignoring the impairment charge completely, the analyst also risks overlooking those original cash expenditures that preceded the impairment. This produces a misleading picture of the company’s actual long-term performance.

The analyst might therefore want to compare the non-GAAP base figures against the historical GAAP performance. Do the two square? Would a projection based upon the non-GAAP results be consistent with the company’s long-term historical GAAP performance?

Non-GAAP Metrics Give the Investment Community Another Tool to Evaluate Company Performance. Despite the concerns about the increase use of non-GAAP earnings measure, sophisticated investors and investment professionals should view them as another tool that can be used to gauge a company’s historical performance and future prospects.

Just as few analysts take reported GAAP net income as gospel and most adjust the GAAP numbers to reflect their assessments of the company’s application of accounting standards or its use of estimates in key line items that determine GAAP earnings, so they may rightfully make similar adjustments to the non-GAAP figures.

Non-GAAP measures also provide a way to gauge management’s aggressiveness in promoting its stock price.

The SEC Should Disallow the Reporting of Adjusted Earnings per Share. Since Adjusted EPS applies the Non-GAAP adjustments to the historical figures, it is a misleading measure. It treats these non-GAAP adjustments, like restructuring expenses, as if they never existed. As noted above, analysts should consider what a company’s future earnings will be when restructuring costs that are rightfully deemed to be temporary go away. Accordingly, it is the disclosure of the specific dollar amount of Non-GAAP adjustments (both before- and after-tax) that is relevant for the analysis.

Consequently, the SEC should prohibit public companies from disclosing adjusted EPS. Investors could then incorporate those Non-GAAP adjustments that they deem most relevant into their projection models to determine future GAAP earnings.

This is the approach favored by Mr. Bernstein in his 2019 Op-Ed (referenced above). He suggests that companies should simply identify the factors that management considers to be usual, non-cash or reflective of other factors that may be relevant in assessing their future performance prospects. This would then put the burden on investors to analyze the data and apply their own judgments to the analysis.

Originally published on September 26, 2016; revised January 11, 2018 and December 14, 2020.

Stephen P. Percoco

Lark Research

839 Dewitt Street

Linden, New Jersey 07036

(908) 975-0250

admin@larkresearch.com

© 2020 Lark Research. All rights reserved. Reproduction without permission is prohibited.

You must be logged in to post a comment.