Shares of Five Star Senior Living (FVE) have performed poorly over the past two years, even underperforming FVE’s peer group, which has significantly underperformed both the health care sector and the broader market. The industry is suffering from a slow but steady decline in occupancy due to the increasing supply of communities and slowing demand growth (for demographic, lifestyle and affordability reasons). Investors are also concerned about the long-term impact of proposed cuts to Medicaid funding under new federal health care legislation. FVE has struggled with declining occupancy and high lease costs under its contracts with its affiliate, Senior Housing Properties Trust (SNH). Although management is taking decisive steps to improve the company’s competitive position and boost revenues, it is unlikely that those efforts will be sufficient near-term to reverse FVE’s operating losses.

Five Star Senior Living (f/k/a Five Star Quality Care) operates 283 senior living communities with 31,830 living units in 32 states. The company was formed by Senior Housing Properties Trust (SNH) in 2000 to operate 54 skilled nursing facilities and two assisted living communities that SNH had repossessed from former tenants. In 2001, SNH spun off FVE, which now trades on NASDAQ. At the end of 2016, FVE operated 253 communities owned by SNH.

Equity Ownership. According to FVE’s 2017 proxy statement, three entities currently hold equity stakes in FVE greater than 5%.

- ABP Acquisition (ABP), which is controlled by Adam and Barry Portnoy, owns 18.35 million shares or 36.7% of total outstanding shares. The Portnoys are the founders of RMR Group (RMR) which controls SNH and FVE. Barry Portnoy is Chairman of RMR and a Managing Director of FVE. ABP acquired 18.0 million shares, nearly all of its equity stake, in a $3 per share tender offer that was completed in November 2016.

- Senior Housing Properties Trust (SNH) owns 4.24 million shares or 8.5% of the total.

- The Thomas Brothers (William and Robert), both individually and beneficially own 3.11 million FVE shares or 6.2% of the total. The Thomases have attempted unsuccessfully to take an activist role at FVE on a couple of occasions.

Properties. FVE’s properties include independent living and assisted living communities and skilled nursing facilities. Independent living (IL) communities (34% of FVE’s total living units) are age-restricted (55+) apartment complexes with pools, fitness centers and clubhouses that offer social programs and activities. Most FVE IL communities provide one-or two meals per day at the central dining room, weekly housekeeping services and social director services in their the base charge.

Assisted living (AL) communities (51% of total living units, of which 11% specialize in Alzheimer’s/memory care services) have many of the same features and amenities of IL communities but with higher service levels. A typical AL living units has one bedroom, a private bathroom and an efficiency kitchen. Services include three meals per day at the central dining room, daily housekeeping and 24 hour availability of assistance with activities of daily living. Professional nursing and healthcare services are usually available at scheduled times or upon request.

Free standing skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) (7%) provide nursing and healthcare services for the elderly in a hospital-like setting. They have private and semi-private rooms with a separate bathroom, shared dining facilities and are staffed 24/7 with licensed nursing professionals.

FVE’s Continuum of care communities (CCRC) (8%) have elements of all three facility types – IL, AL and SNF – on one campus, allowing residents to age in place.

Industry Trends. The senior living industry primarily serves U.S. citizens who are above the age of 85. Currently, the 85+ population is growing faster than the population at large, but at a still modest 2.2% annually, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2014 National Population Projections. After 2020, that cohort’s growth will then rise to 2.9% annually until 2025 and then to 4.6% from 2025 to 2030, as the baby boomer generation ages.

Meanwhile, low interest rates, while helping to boost property values, are pressuring the industry in two ways. First, low rates have encouraged construction of new senior living facilities, especially in areas like AZ, GA and TX, where senior living communities have historically experienced high occupancy rates. Property additions have exceeded absorptions for several years now, which has caused average occupancy rates in both senior living and skilled nursing to decline steadily over time. According to the National Investment Center for Senior Housing and Care (NIC), the average occupancy rate for seniors housing was 89.1% in the 2017 first quarter; annual inventory growth was 3.4% and annual absorption was 2.6%. Despite the decline in national occupancy rates, NIC points out that occupancy levels and trends differ significantly across local markets.

Besides encouraging the growth of new supply, low interest rates have also put downward pressure on seniors’ incomes, both through lower cost of living adjustments on pensions and social security and reduced income on savings. Lower incomes may have caused some seniors to delay their moves to senior living facilities.

Although they are more prone to age-related health problems, including Alzheimers, dementia and frequent memory lapses, advances in medical treatment have also allowed more seniors to function independently for longer periods of time and thus defer moves to senior living communities. Most seniors – some sources say 90% – would prefer to remain in their own homes. Still, the steady growth in the 85+ cohort ensures that the demand for senior housing will rise steadily over time.

Besides the decline in occupancy rates, senior housing operators have been challenged by a steady decline in Medicare reimbursement rates mandated from the Affordable Care Act (ACA). New concerns have risen over proposed Medicaid cuts in the successor to the ACA. The combination of declining occupancy rates and Medicare reimbursement have forced senior housing operators to respond by raising rates on private pay patients and also by seeking additional sources of revenues. Average rates for private pay residents should rise over time, as older residents are replaced with new ones, but the decline in occupancy raises the competition for new residents. Unless occupancy rates begin to stabilize, it is unlikely that senior housing operators will be able to raise rates indefinitely.

Given the problems typically associated with Medicare/Medicaid payments – i.e. low rates, political pressure to lower them further and often delayed payments, FVE has sought to limit its exposure to public revenue sources. The company currently derives 78% of its total senior living revenues from private sources. 88% of its revenues from IL/AL/CCRC communities come from private patients; the rest from Medicare/Medicaid. However, 75% of its revenues from its free standing SNFs come from Medicare/Medicaid, which is consistent with industry averages.

FVE’s Competitive Response. FVE has responded to its ongoing revenue pressures in several ways.

- First, it is focused on upgrading or refreshing its communities to ensure that they can continue to compete successfully with newly constructed communities.

- Second, it has taken steps to elevate the quality of its food service and wellness programs – for example, by partnering with a celebrity chef to upgrade its menu and host events that create positive buzz among existing and prospective residents. It has also adopted a new holistic approach to resident wellness called Lifestyle360, which offer activities and events based upon the five dimensions of wellness: intellectual, social, physical, emotional and spiritual.

- Third, it has brought more of its effort for generating new leads in house, in part by upgrading its digital strategy to reach prospective residents.

- Fourth, it has initiated a “Rehab to Home” initiative to attract patients of all ages who are recuperating from illnesses and injuries, including for example those recuperating from hip or knee replacements. To capture this business, it has converted semi-private units within its CCRCs into private rooms with upgraded features. So far, it has completed four conversions with plans for more in 2017 and beyond. In one case, after converting 24 units at a CCRC community, it achieved annualized Medicare Part A revenue growth of $900,000 or 33%, which helped swing that community’s operating loss to a profit.

- Finally, FVE is shifting its focus from maximizing average rental rates to maximizing revenue per available room (RevPAR), which is similar in approach to the hotel industry. Under the RevPAR approach, FVE will be more willing to discount rates on a case-by-case basis to boost occupancy, if doing so increases overall revenues and profits.

With these efforts, FVE sees an opportunity to boost its average occupancy rate for seniors housing over time from 83.6% currently up towards the current industry average of 89.1% or even back toward its historical peak occupancy rate of 92% achieved prior to the recession. Given recent business trends and the current structure of its arrangements with SNH, higher occupancy levels are a prerequisite for restoring the company’s profitability.

Monthly Rates. FVE reported an average companywide monthly rate of $4,690 per living unit or bed for 2016. Using available industry sources, I have estimated FVE’s monthly rates by facility type. Since wages and benefits account for about two-thirds of operating expenses (excluding SG&A costs), it stands to reason that average monthly rates will correlate with the level of services provided at each type of facility.

FVE does not provide information about its average monthly charges by facility type. Based upon FVE’s own disclosures and input from a couple of readily accessible sources – Genworth’s 2016 Cost of Care survey and rate statistics posted on seniorhomes.com, I estimate FVE’s average monthly rates at $3,150 for ILs, $4,800 for ALs and $6,800 (or $223 per day) for SNFs. My estimates for ILs and ALs are about 55% above the weighted average estimates for the states in which FVE does business. For SNFs, my estimate is about 10% above the weighted average for FVE states and 30% above posted Medicare PPS rates for SNFs.

Three Operating Models. FVE utilizes three different operating models: It leases 189 properties (from SNH and HCP), it owns 26 properties outright and manages 68 properties for SNH for a fee. Under the lease and ownership models, FVE bears all of the costs of operating the facilities – except for capital expenditures on the leased communities. SNH has been covering those capital expenditures on leased communities, which have averaged $22 million annually for the past three years (but it has simultaneously increased lease payments by 8% of the covered capital costs). Under the management model, FVE receives a fee from SNH equal to 3% or 5% of the gross revenues generated by the properties and SNH pays all of the direct costs of operating the properties.

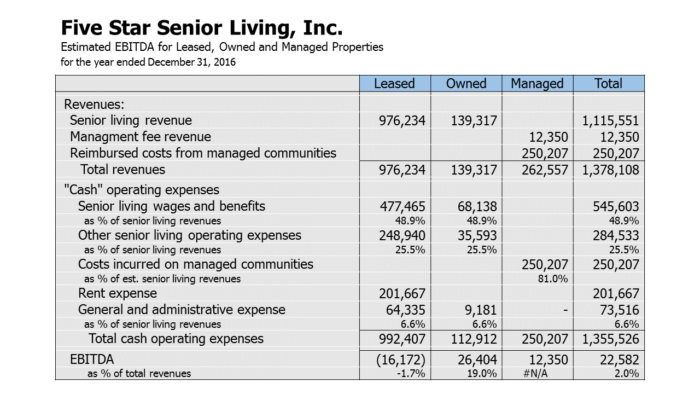

Utilizing my estimates for revenues for each of the property types – IL, AL and SNF – and FVE’s disclosures of property data, revenues and occupancy rates by state, I have allocated FVE’s consolidated revenues and operating costs to each of the three operating models. My estimates indicate that FVE’s leased properties generated revenues of $976 million in 2016, while its owned properties had revenues of $139.3 million.

I allocated wage and benefit costs and other operating costs evenly as a percent of revenues to both the leased and owned properties, even though there probably are differences. (For example, all of FVE’s SNF properties, which probably have higher operating costs as a percent of revenues, are leased.)

Management fee revenues and reimbursed costs are allocated to the managed properties. Rent expense is allocated entirely to the leased properties.

The allocation of $73.5 million of general and administrative costs is more challenging. FVE says that SNH reimburses it for all operating expenses that are directly attributable to the managed communities. That implies that FVE probably bears certain indirect costs – like human resources, information technology, regulatory compliance, state licensing, private pay billing and accounting. It might make sense, therefore, to allocate some G&A expense to the managed properties.

However, reimbursed costs on the managed properties equaled 81% of estimated gross revenues of $308.8 million in 2016. That is exactly equal to FVE’s consolidated operating expense rate (equal to the sum, as a percent of senior living revenues, of wages & benefits (48.9%), other operating expenses (25.5%) and G&A expense (6.6%) ), which reflects operating expenses for the leased and owned properties. It could be, therefore, that SNH is paying for most, if not all, of G&A costs attributable to the managed properties. It is also possible that the managed properties are much less profitable than the leased and owned properties or even that SNH is tacitly reimbursing FVE for costs in excess of the operating costs of the managed properties. In any case, I have decided to allocate all of the G&A costs ratably (as a percent of senior living revenues) to the leased and owned properties only and none to the managed properties.

Based upon my analysis, I estimate that the leased properties generated an EBITDA loss of $16.2 million in 2016, which was entirely attributable to rent expense. The owned properties had EBITDA of $26.4 million. The managed properties had EBITDA of $12.3 million, which equals the management fee revenue that FVE receives from SNH.

As noted, this is a simplified analysis. The leased properties may conceivably be more profitable and the owned properties less profitable than my estimates indicate. Likewise, some G&A expense may be allocated appropriately to the managed properties. Even so, even with a different cost allocation that results in lower costs for the leased properties, it is highly likely that the leased properties are still loss-making and the owned properties provide a majority of FVE’s consolidated EBITDA.

If the leased properties are unprofitable (or even only marginally profitable), then FVE’s rent expense is obviously too high. Most of these lease agreements were structured years ago, when the properties probably had higher occupancy rates and operating profits. Although the leases have been modified from time to time, mostly to adjust for acquisitions and divestitures, the lease payments have remained relatively flat, even as the profitability on all of FVE’s operating properties has declined.

In June 2016, FVE sold seven senior living communities to SNH for $112.35 million and entered into a new lease (Lease No. 5) with an initial annual payment of $8.43 million. (Two other properties were later added to the lease bringing the current minimum payment to $9.82 million.) Starting in 2018, FVE’s lease payment will increase by 4% of revenue growth above the 2017 base. The initial payment equates to 7.5% of the sale proceeds. That is a half point below the average rate of around 8% that I estimate FVE pays on its older leases.

FVE booked a deferred gain of $82.44 million on the sale, which will be amortized as an offset to rent expense over the 11 year initial term of the lease. The amortization of the gain will reduce lease expense by $6.61 million annually.

FVE used the proceeds from the sale-leaseback to pay down $50 million of outstanding borrowings under its credit facility, reduce accounts payable and other liabilities by about $40 million and meet other needs in the ordinary course of business. The sale-leaseback, therefore, was implemented to help FVE cope with its deteriorating financial performance.

Valuation. Given the June 16 closing price of $1.60, FVE’s equity has a market capitalization of $80 million. The company’s loss per share on a rolling 12 month basis was $0.53 per share. Although I have not prepared formal projections for FVE, expectations of continued pressure on occupancy rates from the increasing supply of senior living communities suggest that the company’s net losses will continue over the next couple of years.

FVE has recorded operating losses for 14 consecutive quarters. Its stance on maintaining a valuation allowance for nearly all of its deferred tax assets suggests that it does not see an imminent turnaround in profitability. Management’s efforts to improve FVE’s competitive position, as described above, may help to offset some of the continuing pressure on occupancy rates, but it may be at least a few years before they have a meaningful positive impact on FVE’s overall profitability. Management has not offered any specific guidance on 2017 or 2018 results that suggests that a return to profitability is imminent.

The new lease accounting standard, which is required to be adopted in 2019 but may be adopted earlier, could conceivably cause a change in FVE’s income statement and reported profitability. FVE has indicated that while cash outflows will be unchanged, it expects that amounts within its statements of operations and comprehensive income to change materially. The old rule of thumb allocated 1/3 of the lease payment to interest expense. If applied under the new standard, that could cause 2/3 of the rent payment to be classified as a reduction in lease liability (and thus be removed from the income statement). However, there should be no impact on FVE’s profitability, if FVE also records a Right of Use asset equal to the lease liability upon adoption, because the ROU asset will also have to be amortized (and show up as an expense). Nevertheless, we will have to wait and see the specifics of FVE’s implementation of the new lease standard.

At the June 16 closing price, FVE’s stock was valued at only 51% of its per share book value of $3.16. I think that a case can be made that the value of the owned properties plus the management contract on SNH properties minus FVE’s net liabilities, exceeds the company’s stated equity book value of $158 million. (At a price of $100,000 per unit for the 2,703 owned units plus ten times the annual management fee of $12.4 million minus net liabilities of $123.7 million (including debt), FVE’s implied equity valuation would be $270 million or $5.40 per share. However, that valuation does not reflect the recurring losses on the leased properties or the ongoing pressure on consolidated revenues and profits from continuing declines in occupancy. To some degree, FVE’s structural net loss implies that overall the company is a wasting asset.

Possible Responses to Current Business Challenges. FVE’s rent expense is too high. Given the tough industry operating environment, the company needs to reduce that lease expense, if it has any hope of returning to profitability anytime soon. The simplest solution would call for SNH to reduce its minimum rental charge, but perhaps allow it recoup some of the foregone rental income with growth in FVE’s revenues and/or profits.

In my mind, the reduction in rent should be implemented without any concessions on FVE’s part. However, SNH could conceivably ask for something in return, such as an increased equity stake in FVE. Negotiating such an equity giveback would be tricky, however, because of the interconnectedness of RMR, SNH and FVE. I also think that an equity giveback would have to be struck at much less than a market rate, if it is to have a positive impact on the value of FVE shares held by outsiders. (For example, I think to be meaningful, the cut in rent expense should be on the order of $50 million or about 25% of total lease expense, but the implied value of such a cut – say $400 million, if valued at eight times, far exceeds FVE’s current equity market cap of $80 million.

The increased equity stake of ABP Trust and the Portnoys potentially complicates such a renegotiation, but also raises alternative opportunities. The Portnoys stepped up in November, increasing their risk exposure by paying an above market price of $54 million for their 37% stake. The equity market value of the remaining shares is currently $43.8 million; so it would not be that much of a stretch for the related parties to take FYE private.

Alternatively, FVE and SNH could pursue an M&A transaction which would give them the opportunity to increase operating scale, reduce operating costs and boost their competitive position. HCR ManorCare (HCRMC), which is controlled by the private equity firm Carlyle Group (CG), is behind on its rental payments to its largest landlord. Quality Care Properties (QCP), which was previously controlled by Carlyle, sold to HCP and subsequently spun off in 2016. A combination of FVE and HCRMC (and possibly SNH and QCP) may be a stretch, but it could conceivably help both sides cope in the current environment. Brookfield Senior Living (BKD), the industry leader, is also on the block, which highlights the turmoil being felt across the industry.

Fixing FVE may not be easy to accomplish in the short-term, but RMR and its affiliated companies have several available financial and strategic alternatives and sufficient financial flexibility that should allow FVE to continue to operate and improve its competitive position over time.

June 18, 2017

Stephen P. Percoco

Lark Research, Inc.

839 Dewitt Street

Linden, New Jersey 07036

(908) 448-2246

incomebuilder@larkresearch.com

© Lark Research, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction without permission is prohibited.